No products in the cart.

Transport gratuit pentru comenzile de peste 100 RON.

COȘUL MEU

Derrière la perfection, gifles et insultes: l’ancienne gymnaste roumaine Nadia Comaneci a été rudoyée par son entraîneur sous l’oeil complice de Ceausescu, selon un récent ouvrage basé sur des dossiers inédits de la Securitate.

During the remainder of the Games, where she won three gold medals, she would receive the highest possible score six more times, becoming one of the most iconic sporting legends of all time – as well as a silver bullet for the Romanian regime in terms of international propaganda.

But fame came at a price. Thirty-five years on from her unprecedented feat in Canada, a new book reveals with chilling detail the extent of the round-the-clock surveillance Comaneci endured at the hands of the Securitate secret police, as well as the physical and psychological abuse inflicted on her by her draconian coach, the renowned gymnastics trainer, Bela Karolyi.

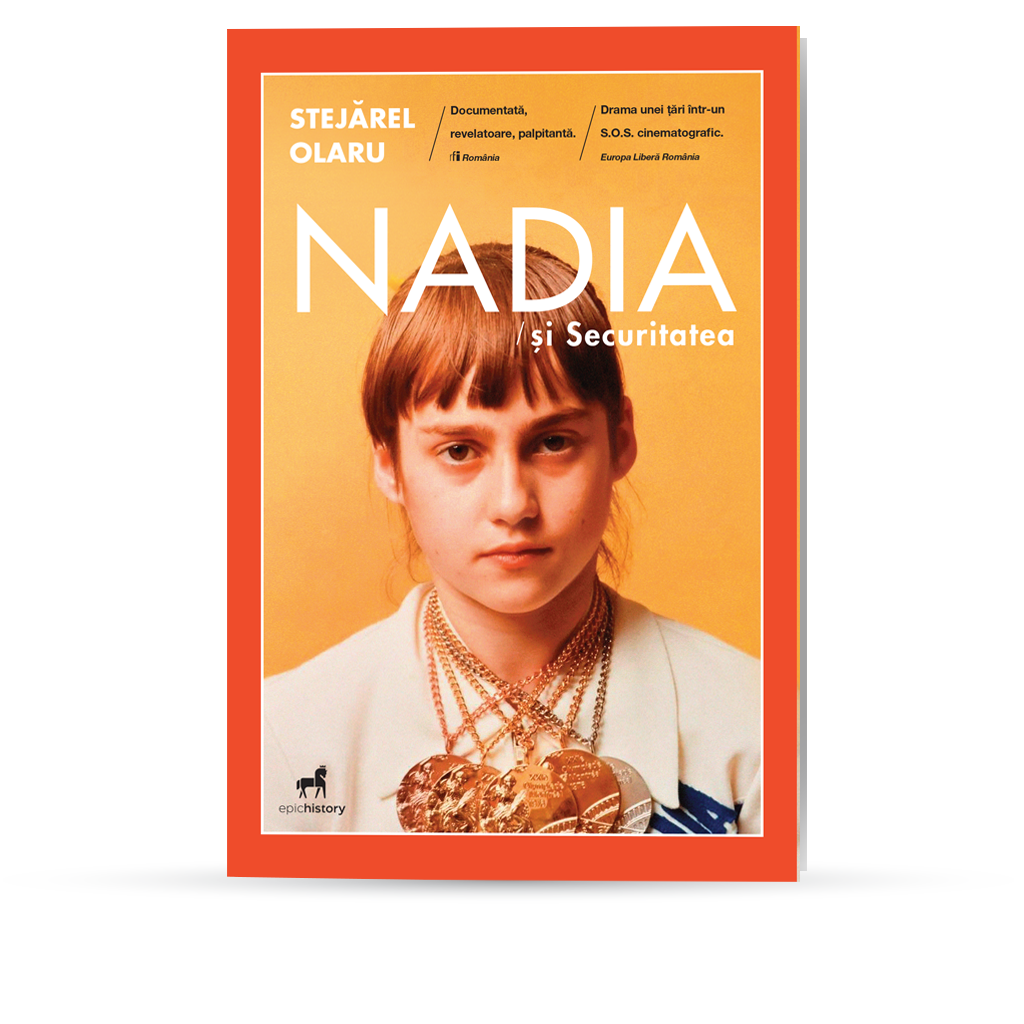

Nadia and the Securitate, by Romanian historian Stejarel Olaru, is a meticulous and ballyhoo-free reconstruction of the ordeal the teenager experienced at home while awards and accolades poured in from abroad – to be cashed in by Romania’s dictator, Nicolae Ceaucescu.

The book draws mainly on the now declassified archives of the secret police, the infamous Securitate.

“She started being surveilled when she was only 13, until 1989, when she fled the country,” explains Olaru, who had extensively researched the Securitate archives before, but confesses feeling shocked at the magnitude of the human, technical and logistical resources mobilized by the Ceausescu regime to control Comaneci.

Since she started excelling in sport in her hometown until the very moment she managed to evade her watchers and illegally cross the border into Hungary on foot, and then seek refuge in the US, virtually all her movements and many of her private conversations were monitored and documented.

Microphones installed in every home she or her family occupied and a legion of informers – including Karolyi, the choreographer of the Romanian Olympics team and the federation officials and journalists who travelled abroad with the delegation – made sure that Ceausescu and his wife, Elena, knew at all times what was the country’s number-one sporting asset was up to.

One of the objectives of this deployment, explains Olaru, was to prevent Comaneci from escaping the country, being kidnapped by what the paranoid regime deemed foreign hostile forces, or defecting to the West during competitions held on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

In some instances, the rifts between Nadia and her coach prompted the teenager to run away from training sessions, after which the Securitate would locate her and bring her back.

Leading Communist Party officials, including Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu, intervened personally more than once to defuse tensions, return Comaneci to her coach, or assign her other trainers, so she could continue bringing international glory to Romania.

There were other motivations to keep all those eyes trained on Nadia. The regime needed to ensure that Comaneci did not relax and kept observing the spartan lifestyle required to perform at the highest level.

The tense relationship between Comaneci and her teammates and Karolyi was another main source of concern; the teenager was becoming increasingly angry and frustrated with the methods of her coach, who used to hit and insult his gymnasts when they failed, and force them to compete and train even when they were injured, against the advice of the doctors.

“This abusive treatment, which was widespread in the Communist bloc, was known in sporting circles, but not by wider society at the time,” Olaru said. “The regime wanted to hide the constant conflicts,” he added.

Nadia and the Securitate is rich in details of the constant feuds between Comaneci and Karolyi. In one of the notes reproduced in the book an informer reports on Comaneci recounting in a private conversation how she was obliged to stay in a sauna “until we felt sick”, or how she was often called “fat” and “an imbecile” by Karolyi, who once forbade her from eating for three days so she could lose weight to compete.

Despite her rebellions badly affecting her training at times, Comaneci remained a source of international praise for her country until she retired after the 1980 Moscow Olympics, at which she won two further gold medals.

“Other athletes had most likely been expelled from the team, but Nadia was an exception; Romania needed Nadia because Elena [Ceausescu] wanted her medals,” Olaru said, explaining why a regime hardly known for its sense of fair play tolerated her occasional acts of insubordination.

Comaneci’s situation worsened after Karolyi and his wife and fellow coach, Marta, defected to the US during an international tour in 1981.

Fearing that she would follow in their footsteps, the regime stepped up its already suffocating surveillance.

Nadia had also in the meantime become romantically involved with the Ceausescu’s favourite son, Nicu, which intensified Elena’s obsession with a young, talented woman she had always been suspicious of.

These circumstances led the regime to drastically limit Comaneci’s travel abroad. However, a rare chance for foreign travel arose in 1984, for the Los Angeles Olympics, where she attended one of the gymnastics finals at the Memorial Coliseum.

When the cameras projected her face on to the stadium’s screens, 80,000 spectators cheered. From homes across the globe, millions of others saluted the young Romanian whose immaculate performance eight years ago in Montreal had entranced them.

As Olaru notes in his book, they could not imagine that their heroine “was living a life full of restrictions on a salary of approximately 150 dollars a month” as a gymnastics federation official, and under the close watch of the dozens of “officers and informers of the Securitate” who “grossly invaded her privacy without any limits”.

Nadia left all this behind on the night of November 27, 1989, when, together with a group of fellow Romanians and guided by a shepherd with extensive knowledge of the area, she joined thousands of other desperados pursuing freedom, and clandestinely escaped across the border into Hungary.

Among other things, Nadia and the Securitate is a sobering psychological portrait of Comaneci, who the Securitate archives reveal as a brave, tenacious, gregarious and down-to-earth girl and then woman, who never let herself be swallowed up by fame or succumb to the temptation of self-pity.

She also refused to play the victim card from the safety of the US. Comaneci has never publicly condemned the coach who, for all his faults and harshness, made her the prodigious gymnast she will always be remembered as.

Olaru told BIRN that she declined to be interviewed for the book but consented to go through some of the secret police documents filed on her, so her former coach could have a fair “trial” in the book.

Nadia’s cooperation helped the author discern truth from malicious exaggeration, or the outright lies inevitably contained in the Securitate reports – resulting in this eye-opening account of the Olympic legend and her era.

Toate cărțile comandate de pe site-ul nostru se vând cu reducere de 25%. Pentru toate comenzile de pe site-ul nostru costul transportului este de 17 lei, această sumă adăugându-se la prețul final. Vă rugăm să specificați titlul complet, autorul, numărul de exemplare, numele și prenumele (așa cum apare în actul de identitate), adresa și numărul de telefon. Vă mulțumim pentru că ați ales să cumpărați direct de la noi.

Copyright © Editura Omnium. All Rights Reserved 2021.